Research

Working papers

Postharvest Losses from Weather and Climate Change: Evidence from a Million Truckloads (With Tim Beatty)

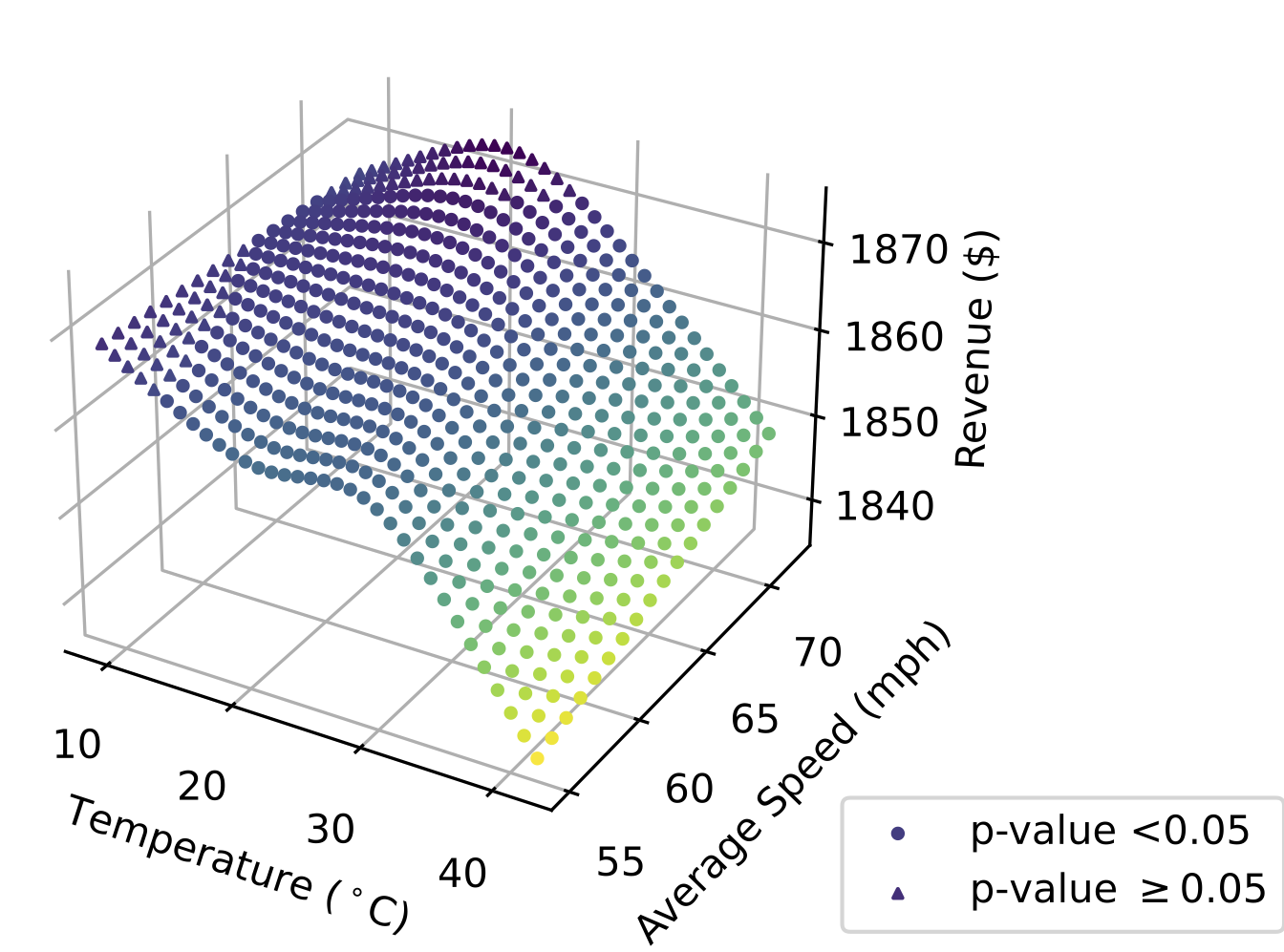

We estimate the effect of weather and climate change on postharvest losses from data on 1.2 million truckloads of processing tomatoes in California. Our reduced-form estimation strategy compares processing tomatoes grown in the same field in the same season but experience different weather and traffic conditions during transit. Hot temperatures during transportation damage product quality and lead to lower producer revenue, particularly when hot temperatures coincide with heavy traffic. While effect sizes are small in absolute terms, hot temperatures during transportation cause about three times more damage than equivalent exposure during the growing season. We predict climate change will increase postharvest losses by century’s end absent additional adaptation. We add to prior work focused on farm output with little attention paid to effects of extreme weather and climate change on products after they leave the farm.

Climate, Weather, and Collective Reputation: Implications for California’s Wine Prices and Quality (With Julian Alston) Link

Wine is the most differentiated of all farm products, with much of the differentiation based on the location of production. In this paper, we estimate the effects of climate and vintage weather on California’s varietal wine quality and prices. We use a sample of premium wines rated by Wine Spectator magazine and a comparable sample of secondary market auction prices from K&L Wine Merchants, matched to spatially detailed weather data from PRISM. We find that extreme temperatures, particularly extremely hot temperatures, caused prices to decline and that climate change will harm wine quality and disrupt quality signals from geographical indications.

Doing More with Less: Margins of Response to Water Scarcity in Irrigated Agriculture

Adapting to less water is critical to a food-secure future in light of an increasingly variable and scarce water supply. Farmers respond to water scarcity by changing if they plant and what they plant, but there is inconclusive evidence on whether farmers change how they produce. I analyze farmers’ decisions using a panel of 3,300 irrigated fields in California from 2011–2021. I use novel proprietary data on growing practices collected by a large tomato processor. It provides evidence of the mechanisms by which growers use water more efficiently – insights unattainable in publicly available or survey data. I find that during a water scarce year, tomato growers are more likely to plant earlier, plant fast maturing varieties, and preferentially plant fields equipped with drip irrigation rather than less water efficient technologies. Water access priority drives how growers conserve water: growers with low-priority access rely on more costly margins, such as fallowing or changing growing practices in ways that reduce revenue. This demonstrates that agricultural producers engage in water-saving practices more than is typically assumed and that these practices help growers avoid fallowing, a much more costly response.

Climate Change and Field-Level Crop Quality, Yield, and Revenue (With Tim Beatty) Link

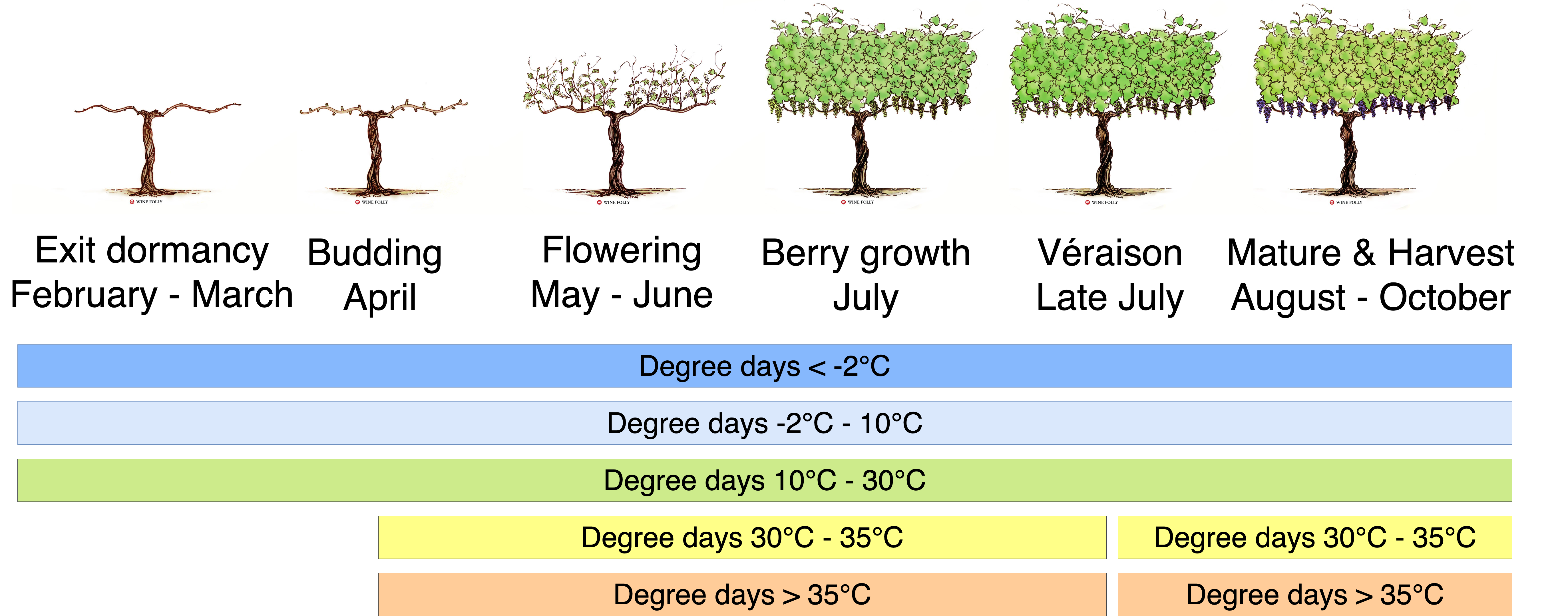

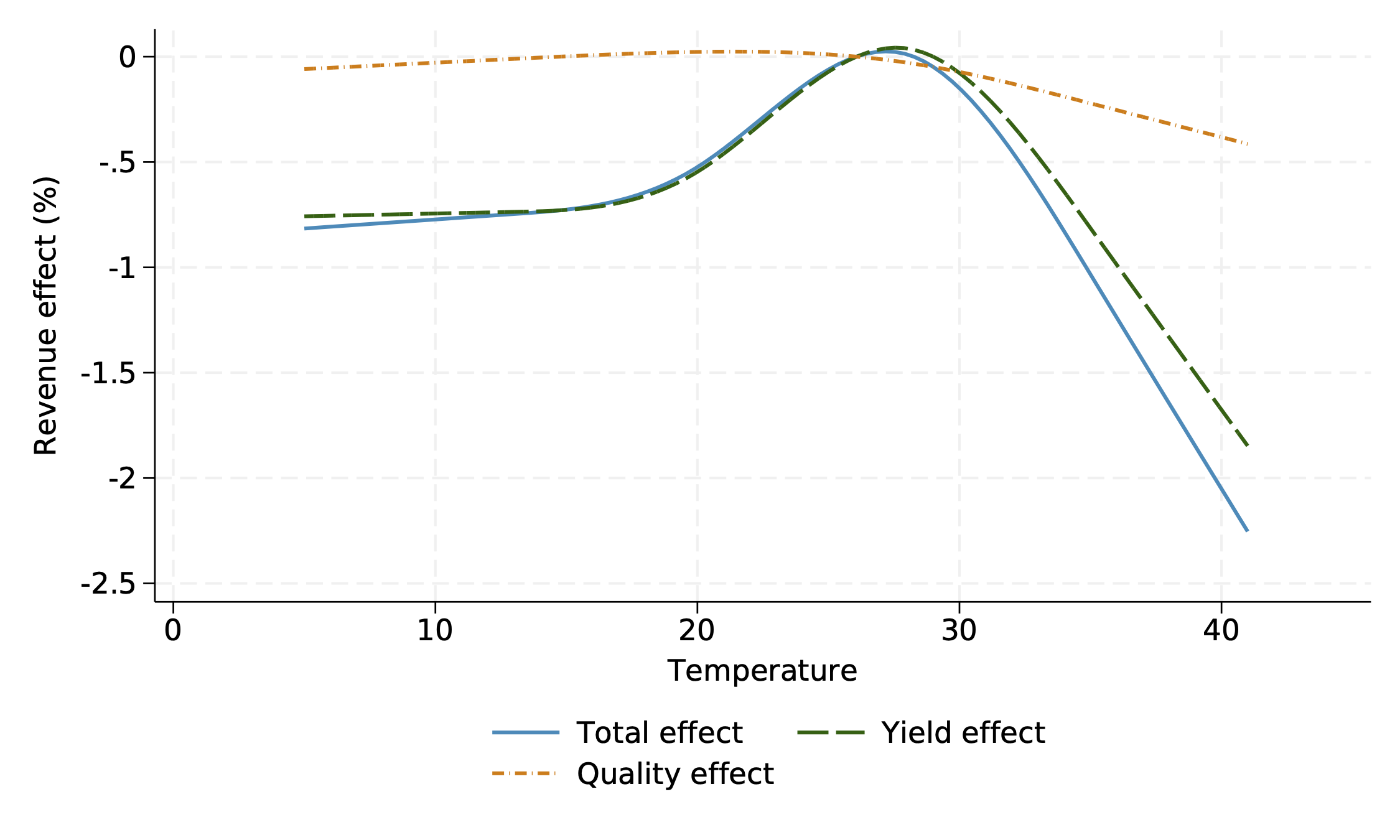

We quantify the effect of weather and climate on the revenue of processing-tomato farmers through yield and quality—quality being an understudied channel despite its role in price determination. The widespread practice of screening out low-quality products introduces selection bias into most estimates of the effect of weather and climate on agriculture. Our novel field-level data allow us to estimate the magnitude of this bias. In contrast to earlier work on irrigated crops, our study finds extreme temperatures reduce both processing-tomato yield and quality, leading to reduced revenue. While the yield effect dominates, failing to account for the quality effect leads to a significant underestimate of the effect of temperature exposure on revenue—up to 12%. We predict climate change will significantly reduce yield and quality by century’s end absent additional adaptation. Yield effects are overstated while quality effects are understated when estimation relies on data on a subset of output that exceeds a quality threshold. Empirical work on any agricultural product that fails to account for selection on quality may misrepresent the climate change challenge.

Press: National Geographic

Publications

Cuffey, J., K. Newby, & S. Smith (2024). Social Inequity in Administrative Frictions: Evidence from SNAP. Public Administration Review, 84(2), 338-356. Link

Smith, S. C. & D. Ubilava (2017). The El Niño Southern Oscillation Cycle and Growth in the Developing World. Global Environmental Change 45, 151-164. Link

Outreach Material

Smith, S. (2017). Wheat. Agricultural Commodities: December quarter 2017 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Smith, S. (2017). Wheat quality explained. Agricultural Commodities: September quarter 2017 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Smith, S. (2017). Wheat. Agricultural Commodities: September quarter 2017 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Smith, S. (2017). Wheat. Agricultural Commodities: June quarter 2017 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Smith, S. (2017). Wheat outlook. Agricultural Commodities: March quarter 2017 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Smith, S. & A. Cameron (2017). Horticulture outlook. Agricultural Commodities: March quarter 2017 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Brown, A., J. Fell, S. Smith & H. Valle (2016). Australian grains: Outlook for 2016–17 and industry productivity. ABARES report prepared for the Grains Research and Development Corporation ABARES, Canberra.

Smith, S. (2016). Wheat. Agricultural Commodities: December quarter 2016 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Smith, S. (2016). The EU almond industry. Agricultural Commodities: September quarter 2016 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Smith, S. (2016). Wheat. Agricultural Commodities: September quarter 2016 ABARES, Canberra. Link

Smith, S. & J. Hogan (2016). Trade in fresh fruit and vegetables. Agricultural Commodities: June quarter 2016 ABARES, Canberra. Link